Venture Capital Term Sheet

Nic Mahaney

Prev. OnePager Co-Founder

September 8th, 2021

Negotiating a Term Sheet With Investors

In term sheet negotiations, there is typically informational asymmetry. The Venture Capitalists (VCs) have been through the process many times, while the entrepreneur may have never negotiated such a document before. This makes it important for the entrepreneur to not only have a good lawyer but know what they want (Nivi).

VCs have two main interests in negotiating a term sheet: Economics and Control (Feld). “Economics” refers to terms that affect the end-of-day return that investors will get, and “Control” refers to mechanisms that allow investors to control the business and veto certain decisions (Feld). While VCs certainly desire success from the companies they've invested in, they are ultimately vying for terms that will best serve their fund and their investors (Nivi).

Hiring a Lawyer

One of the most important steps an entrepreneur must take in order to ensure that they have a solid stance in term sheet negotiations is hiring a lawyer.

Don't Put it Off

You should hire a lawyer at the earliest possible date, even if you have to negotiate a deferred payment plan. Early legal blunders can lead to serious problems for your company later down the line, therefore it's better and easier to make sure you’re legally sound from the very beginning (Suster).

Go Local

All law firms are not created equally when it comes to VC term sheet negotiation. If possible, you should hire a local firm. You can easily walk into their office and build a relationship, they can help tap you into funding sources, and they will often invite you to events where you can meet their other clients (Suster).

Size Matters

Additionally, you want to hire the right sized firm. Don’t just go with the biggest ones; the mega-firms will likely be spending most of their resources on their huge clients (Suster). You also want to make sure that you hire a lawyer with extensive experience with venture financings (Tango)(Westwood) (Suster).

Experience is Important

Inexperienced lawyers have a higher chance of giving you a strategic disadvantage, as they are not as familiar with the nuances of VC term sheets and might push hard for irrelevant terms and concede crucial ones. This creates a more hostile negotiation and might result in a worse deal for the founder. Good lawyers can educate founders on key terms and can understand their relative significance.

Understanding Term Sheets

Term sheet negotiations can be extremely complex, and it can take many years to develop a mastery of the process. However, there are some negotiating tactics you can keep in mind as a founder to ensure you get the best term sheet possible.

Prioritize Your Interests

You and the VC have competing interests, and neither of you will get everything that you want out of the negotiations. Thus, you should make a list of your top 3 most important issues to prioritize in the negotiations (but don’t be aggressive or unreasonable). Let your attorney know what these key issues are so they know what to fight hardest for. (Tango)(Bartus).

Stand Up for Your Cause

Don’t accept the term sheet as-is. Smart negotiating shows investors you will stand up for important issues and you know what you are doing (Bartus).

Gauge VC Interest

If you can, quantify the VC’s interest level. Most term sheets will have a “no-shop clause,” which is a guarantee that the founder won’t go to other VCs searching for a better deal or to entice the VC to offer a better term sheet (Feld). Thus, you don’t want to waste time trying to close a deal with a VC that isn’t really interested (Tango).

Organize a Signing Party

The process of passing documents between the VCs, founders, and both parties’ lawyers can take many weeks. If you can get everyone to agree to it, hold a “signing party” wherein everyone meets at a physical location for a few days and you can negotiate the term sheet in-person. This can save lots of time and money in legal costs (Suster).

Be Personal

While it is extremely important to have enough technical knowledge to navigate the negotiation process without making dire blunders, negotiations are an inherently interpersonal exercise. Founders should use the following advice and their common sense to negotiate in such a way that conveys their professionalism.

When working on a deal, don’t just have your lawyers mark up a bunch of documents and send it to the person with whom you’re negotiating. This can be frustrating and considered rude. Instead, call or meet face-to-face with the recipient and walk them through the things you need changed. This way, they can understand where you are coming from, increasing your chances of working out any differences. (Wilson).

Additionally, you always need to remain calm. Establishing a good relationship with the VC is crucial, and becoming overly emotional or erratic during these negotiations may signal that you have difficulty making decisions under pressure (Tango).

It is also extremely important to be honest throughout this process. You don’t have to tell the VC everything, but do not mislead or lie to them. That is a horrible way to begin a relationship, and the truth will come out eventually (Tango). Lastly, own the negotiations- don’t expect lawyers to negotiate for you. Your attorney should be your sounding board, but you should lead the negotiations and advocate for your best interests (Tango)(Suster).

What are some standard terms?

It’s difficult to develop clear standards for what terms are fair or favorable to founders, as it really depends on the context of negotiations. However, below are some standards and pieces of advice provided by various authors. These are meant to give you a better frame of reference in your term sheet negotiations and hopefully steer you clear of agreeing to painful provisions. We recommend following the links provided to learn more about the rationale behind each of these suggestions. Then, apply that rationale to your own negotiations.

Equity/Valuation

- More than 30% dilution is not advisable in any funding round (Shrivastava).

- “Anti-dilution provision” refers to an investor’s right to purchase additional shares of stock at later rounds of fundraising in order to preserve their percent ownership in the company (Ehrenberg).

Board Control

- Offer a maximum of one seat per round (Shrivastava).

- Founders can try to maintain control of the company by creating a board that reflects the ownership of the company and creating a new board seat for a new CEO (Navi).

- It is traditionally pretty rare for the founders to control the board after series A (Walker)(Glazer).

- Usually there is a compromise in board control in which the “tie breaking” member is a mutually agreed-upon 3rd party (Walker)(Glazer).

- You should also push for the investor to actually name a representative on the board to avoid them sending over a junior staffer instead of a heavyweight partner (Walker).

- The investor investing the most money (“lead” investor) will often request one board seat (Walker).

Hiring

- Be wary of clauses restricting founders from hiring staff without investor approval (Shrivastava).

Expenses

- Negotiate hard on clauses requiring founders to get investor approval on any major expense (Shrivastava).

Liquidation

- 1X liquidation preference is the best (Shrivastava)(Arrington)(Wilson)(Glazer).

- Liquidation preference refers to the amount of money an investor will receive if the company liquidates. It is expressed as a multiple of the initial investment (usually starts at 1x - meaning in a liquidation event, investors will get back $1 for every $1 they put in). If a company is doing poorly or in bad circumstances, investors may attempt to negotiate it up to 1.5 x or 2x and beyond in extreme cases. Generally, where there are not enough funds to pay out everyone as part of liquidation, it will require that the preferred holders be paid before founders/employees (Glazer).

- You want to negotiate for no participation with preferred stock. When there is participation, VCs get their liquidation multiplier back AND are able to participate pro-rata in a sale (Arrington).

Discounting

- Negotiate any clauses calling for a discount in future funding rounds on valuation (Shrivastava).

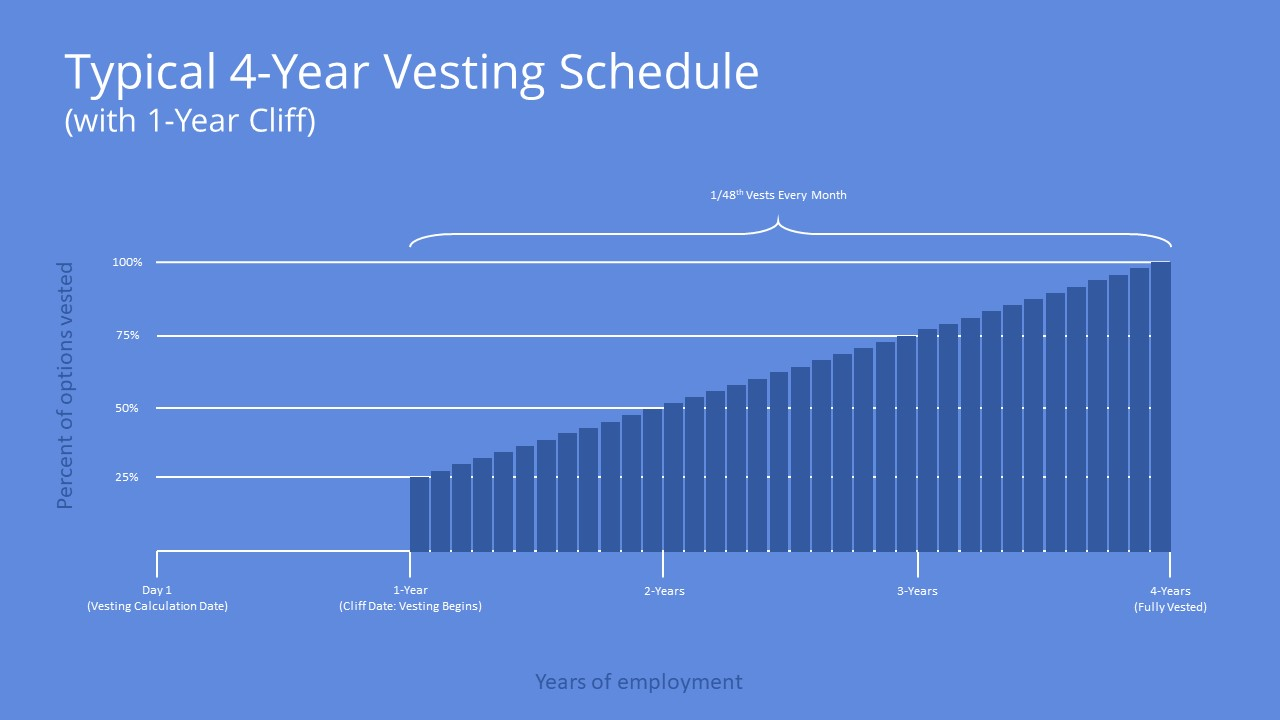

Vesting

- Vesting exists to protect founders and investors. Imagine the following scenario: you and your co-founder both own 40% of your company, and your co-founder decides that he/she wants to leave the company. Without any vesting in place, he/she would leave still owning 40% of the company. With a vesting schedule in place, the company can buy back some or all of the exiting co-founder’s shares. When a founder is issued shares under a vesting schedule, the company has the right to repurchase those shares if the founder leaves the company. Gradually, the right to repurchase those shares lapses (Startup Lawyer). Thus, the longer a founder is at the company, the more of their shares they will be able to keep when they leave, up until the point when their shares are fully vested.

- Make sure that you negotiate through clauses barring founders from leaving their companies under any circumstances for at least 5 years (Shrivastava), as this can be a dangerous clause intended to lock you into the company.

- There is no clear consensus when it comes to what the best vesting provisions are for founders. Arrington advises that you want to negotiate for single trigger vesting acceleration on acquisition (Arrington). Wilson, however, disagrees, as he prefers double trigger (company is acquired and you are fired) with partial single acceleration on single trigger (company is acquired and you remain at the company)(Wilson). VCs like double triggers because it’s easier to sell a company whose founders are locked in (Arrington).

- Dixon argues that all startup employees should vest over 4 years, with a 1 year cliff (Dixon). Not only is it unfair for an early, non-participative partner to hang on to a ton of equity, but it also means there is less equity to give out to future employees.

Things to Watch Out For (General Advice)

Signing a Term Sheet

It is of utmost importance that a founder never sign a term sheet they don’t completely understand. It is the founder’s responsibility to fully understand a term sheet before signing it; don’t hesitate to ask questions and push back on clauses (Destin).

Don't Rush Negotiations

Make sure you don’t agree to substandard terms for the sake of speeding up your negotiation. Series A terms tend to be the baseline for future fundraising. It can be difficult to drop or negotiate unfavorable terms later; future investors may be reluctant to do so.

Avoid Automatic Conversion Terms

Don’t allow investors to negotiate different automatic conversion terms for different series of preferred stock. This could end up in one series’ stockholders’ automatic conversion not triggering, effectively giving them a veto power over the IPO (Feld).

Remain Civil

Don’t slander VCs who pulled out of your term sheet. Bad-mouthing the VC who pulled out of your term sheet is a bad idea; most people don’t like people who bad-mouth others and at worst, some will assume there was something wrong with you or your business. It is better to wait for a cooling-off period and warn other founders 1-1 in private if appropriate (Suster).

Save Money and Do It Yourself

Don’t have your lawyers do things that you can do yourself. The founder should not waste money having expensive lawyers do things that they can/should easily do for free (should be practical about what to ask lawyers to do)(Suster).

Things to Watch Out For (Terms)

Keep the Term Sheet Simple

You don’t want the term sheet to be too complex. When the term sheet is too complicated, the founder and the investor can end up spending an enormous amount of time disagreeing about how clauses should be applied and less time on focusing on nailing business execution and growth, which is how value is actually created (Destin).

Be Weary of Review Period Clauses

Avoid signing term sheets with review periods and no-shop clauses if the VC has not done much due diligence. Review periods allow investors to pull the term sheet after it’s been signed. The founder should be wary of investors who include review periods but have not actually done enough diligence (e.g. customer engagement data, the competitive landscape, and market trends) because it is likely that they have not built enough conviction to put down a term sheet. Review period clauses are especially concerning when accompanied by a no-shop clause which effectively prevents founders from talking to other potential investors (Marion)(Wilson).

Don't Lose Control

Founders should be wary of terms granting investors a high level of control. When reviewing a term sheet proposed by a potential investor, the founder should specifically look out for asking for too large of a controlling stake, which may suggest that he/she will be replaced (Cremades).

Investor director’s approval provisions can lead to founders losing operational control of the company (setting the annual budget, hiring/firing executives, pivoting the business, etc). Founders should try to steer them away from investor director’s approval provisions and negotiate on valuation to address risk, while getting more standard terms (Kwon).

Substandard/controversial protective provisions that founders should push back on include: any hiring, firing or change in the compensation of any executive officers; the entering into any transaction with any director, executive or employee of the Company; any incurrence of indebtedness in excess of $100,000; any change in the principal business of the company or the entering into any new line of business; any purchase of a material amount of assets of another entity.

Founders should also watch out for high voting thresholds (66% is appropriate). There should also be a minimum percent (e.g. 25%) of the original preferred stock remaining in order for protective provisions to apply; so that “you don’t have one guy holding one preferred stock getting to trigger all the protective provisions," (Walker).

Founders should also be careful to negotiate on downside protection provisions. Accepting any term including a guarantee of the exit horizon, which is an expected payment within a pre-planned timeline, lowers the founder’s negotiating power in an acquisition scenario as potential buyers will realize that they are under pressure to close a deal (Marion).

Preferred Stock Liquidation Preference

Another potentially dangerous term that was previously mentioned is including multiple liquidation preferences. This clause allows investors to get a multiple of their money back before the founder gets anything. The founder can accept this clause to get the VC to accept a higher valuation (risky, but up to the founder). If the company goes public (which will convert preferred shares into ordinary shares, making the liquidation preferences disappear) or the liquidation preferences are negotiated in a subsequent round of finding, the founder wins (Destin).

Dividends in Arrears on Cumulative Preferred Stock

Founders should also watch out for terms calling for cumulative dividends (Ackerman). Most dividends get paid out only if the board chooses to do so, but cumulative dividends are required payments to the investor, whether or not the company can afford them.

In most cases, they are basically a way to sneak in an increase in the liquidation preference because the investor knows the company is not going to be able to pay the dividends until a liquidation event occurs (Robinson). This is not appropriate for most VC deals, but could be part of an acceptable trade-off like multiple liquidation preferences (Destin).

Typically combined with cumulative dividends, payment in kind (PIK) dividends provisions state that the required dividends will be paid out in company stock; instead of giving the investors a certain amount of cash every year, the company is obligated to give them a larger and larger equity stake - without them putting in any more money. These should be avoided if possible (Robinson).

Full Ratchet Anti-Dilution

Founders should watch out for terms calling forfull ratchet anti-dilution (Ackerman). Anti-dilution is to protect the investor if the price/share of the company goes down in future rounds of financing; when there is a down-round (i.e. subsequent financing at a lower price per share), the investor receives additional “bonus” shares as protection on share price reduction.

Anti-dilution is usually mild, but full ratchet anti-dilution whereby the number of shares issued to the investor is fully readjusted in case of a down-round can make the founder lose their ownership. There is usually a shared responsibility in full-ratchet: the founder is obsessed with maximizing the valuation and accepts anti-dilution as a tradeoff (taking the risk of losing ownership in case of a significant down-round) (Destin).

Adverse Change Redemption Clause

The “adverse change redemption” clause should also be avoided, as it allows VCs to force a refund if there is a negative change to the business environment or prospects (Feld).

Short Option Exercise Periods

Founders should also fight against short option exercise periods when an employee leaves. Many stock option plans limit the window in which employees can exercise their vested options after leaving the company to 3 months. This means they have to pay the strike price that the options were issued at and acquire the shares, forcing them to spend lots of cash and often crystalizing tax liabilities (which is harsh on the employees).

The founder should try to get a longer window so that people who have contributed to the wealth creation process can share in the wealth when the value is realized (i.e. when the company reaches a greater maturity or is sold) (Destin).

Reverse Vesting

Finally, do everything you can to avoid terms that include unqualified reverse vesting (Destin). A typical reverse vesting provision is a quarterly reverse vesting of founder stock over 4 years. However, unqualified reverse vesting whereby founders lose their stock when they leave their company is very toxic and should be avoided - “You are now fire-able at will and there is even an economic incentive to do so.”

Founders should also make sure there is a “good leaver/bad leaver” clause which means “You get fired for cause, you lose some. You decide to leave, you lose some. The company decides it does not want you around anymore, you keep it,” (Destin).