The Spectrum of Capital

Nic Mahaney

Prev. OnePager Co-Founder

September 1st, 2021

Introduction

Chapter one of The Founders Guide to Fundraising will explain in detail the spectrum of capital, who offers what, and why certain options are offered. First, we will discuss public and private capital.

What is Capital?

Capital is just money, but understanding capital isn’t as simple as it sounds. Capital falls into many categories and can come from many sources. As a founder, understanding the differences can be a matter of reaching profitability or going bankrupt. There are four main types of capital: debt, equity, working, and trade (Hargrave). Furthermore, capital can come from public or private marketplaces.

Types of Capital

Capital can be divided into debt, equity, working, and trade (Hargrave). While fundraising, founders should focus on debt and equity capital. Similar to public and private, debt and equity describe the source of the capital. Debt capital is capital acquired from taking on debt and equity capital is capital acquired from selling equity (Hargrave). Debt and equity fundraising will be covered more in-depth later in the chapter.

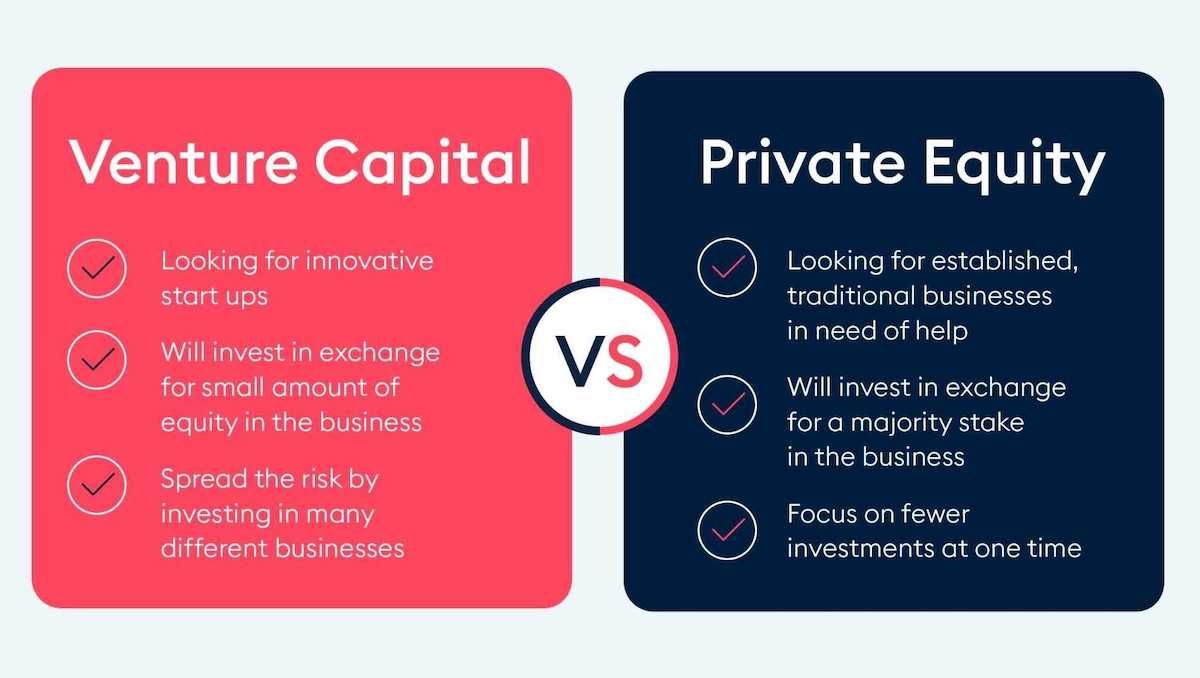

Private Equity Vs. Public Equity

Public and private describe the source of capital. The difference between private equity and public equity is the ownership of shares. Private equity means the ownership of shares in a private company while public equity means the ownership of shares in a public company.

For example, a public company has gone through an initial public offering, allowing the general public to purchase the company’s equity. Meanwhile, a private company may only sell its equity privately and must rely on private funding (Majaski). This private capital is usually sourced from accredited investors, who are either individuals with a high net worth or institutions like banks or large funds (McFarlane).

From an investor’s perspective, private companies are riskier than public companies. This is because public companies must adhere to the policies and regulations enforced by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) (McFarlane). The SECis a U.S. government agency that protects investors by regulating the securities market and exposing fraudulent or manipulated data (Chen).

Furthermore, the majority of large, established, multi-billion-dollar companies are public. To compensate for the higher risk, private investments often have higher potential payoffs than their public counterparts. It is important to keep in mind public companies have large audiences of investors and therefore the company’s equity can be considered a liquid asset (McFarlane).

Sources of Startup Capital Funding

Many parties are willing to fund startups, but obtaining capital comes at a cost. Common sources of capital funding for startups include FFF (family, friends, and fools), angels, angel groups, syndicates, and venture funds. Each of these parties invests for different reasons and provides varying amounts of support and capital (Ward).

Angels, angel groups, syndicates, and venture funds are all in the private sector as they are run by individuals (Chappelow).

What is 'Friends, Family and Fools' Funding?

FFF is the cheapest source of startup funding and founders often turn to this party first (Cavendish). These are the people who would support a founder even if they knew nothing about the startup’s business model.

These people may be eager to get involved, but remember who they are - just friends, family, and not professionals in the industry. Even if they are family and friends, when accepting their money do not wave off the legalities.

Founders must be sure to properly document any terms or conditions they may have in the case a relationship turns sour (Cavendish). This money can help founders get started, but may not last very long.

What is an Angel Investor?

Angels are individuals with a high net worth and are accredited investors. They invest their own money into private companies, and can therefore also be called private investors (Ganti).

Angels can be divided into two groups (Cavendish). The first group invests for a profit. These angels will require founders to pitch their startup and rigorously question them. The second group of angels is more laid back. These angels are less driven by profit as they care more about the entrepreneur than the business.

Many angels earn their wealth from their own successful startups, perhaps with the aid of private investments. They write checks as a form of giving back, paying it forward, or simply because they have a passion for fostering innovation and entrepreneurship (Cavendish).

Advantages and Disadvantages of Angel Investors

There are a number of advantages and disadvantages of angel investors, making them more suitable depending on the type of relationship you're looking to build with your investors.

What are The Advantages of Angel Investor Funding?

Generally, angels are extremely founder-friendly. They aren’t savvy or persistent about their liquidation preferences and don’t seek control requirements (Ward).

Angels are unique because their investment decisions are ruled by a single person: themselves. For this reason, angels are an extremely flexible source of capital. They can write checks the moment they have a reason to.

What are The Disadvantages of Angel Investor Funding?

The tradeoff for the speed and freedom angels possess is the amount of capital and connections available to the founder (Ward). The amount of money an angel can transfer you pales in comparison to a Venture fund or an institutional syndicate. A check from an angel normally falls in the $5k-$100k range, whereas other parties can provide millions of dollars (Ward). The same applies to connections.

Angel Investor Groups

Angel groups are organizations of many angels. These organizations invest for-profit and have a substantially larger presence than lone angels.

Angel groups can accurately evaluate startups, equip founders with both capital and connection, and even lead rounds. The average investment size is between $200k and $300k (Ward). In many ways, an angel group is the opposite of a single angel. Angel groups are extremely slow, have more demands, but can follow up on future rounds and connect founders with a variety of important people.

Angel groups also have strong liquidation preferences. When negotiating, angel groups will often demand preferred stocks and other rights, commonly pro-rata, information rights, and updates.

Syndicate Investment

Syndicate investments function similarly to angel groups, with slight variations. Syndicates have the capability of investing more than angel groups and can provide follow-up funding reliably. However, they are often less involved when it comes to helping a founder expand his/her network.

Syndicates are also considerably faster than angel groups at getting back to founders. Apart from these tradeoffs, syndicates function just like a large angel group (Ward).

Venture Funds

Venture funds include both venture capital and venture debt.

Venture Capital vs Venture Debt

Venture debt functions similar to a bank loan, rendering it less relevant to early-stage startups. On the other hand, venture capital involves the trading of capital for equity in a company.

Investment size depends on the fund size, but venture capital firms can provide the most capital and provide follow-up funding easily. When it comes to outside help and industry experience, these firms are the best out of all parties (Ward).

Venture Capital Advantages and Disadvantage

Venture capital firms can help founders hire executives, establish business partners, find clients, provide strategic and operational guidance, and more (Stanford).

Unfortunately, there is also a tradeoff here. Venture capital firms move slowly, falling between syndicates and angel groups in terms of decision making. These firms are also the pickiest as they purely invest for profit. They have a ‘my way or the highway’ approach to liquidation preferences (Kanies); they negotiate valuations and often demand board positions and other expensive rights (Ward).

Venture capital firms can bring many problems to the founder, including founder oustings (Jackson); they can often promote unsustainable growth and create unreasonable financial conditions (Ward).

The Founders Guide To Fundraising focuses on exploring possible relationships with Venture Capital firms and will cover a wide variety of topics in further detail throughout the whole writing.

Debt Financing Vs. Equity Financing

Capital can be acquired from taking on debt or selling off equity and there are pros and cons to financing through both strategies. Before exploring these however, it is important to develop an in-depth understanding of debt and equity.

What are Debt and Equity Funds?

Debt financing occurs when a founder raises capital by selling fixed-income products, such as bonds, notes, and bills. When this happens, the lender buys the fixed income product, providing the founder with a principal -- capital amounting to the size of the investment loan. This principle must be paid back to the lender at an agreed date, along with additional interest payments (also known as coupon payments) (Chen).

Oftentimes, when taking on debt, collateral will be demanded. Founders should differentiate personal and business credit or collateral may become extremely pricey (Cremades). It is important to understand that when a startup goes bankrupt, lenders get paid back before shareholders (Chen).

When a startup utilizes equity financing, founders have no obligation to repay the capital acquired. Instead, the founder is agreeing to sell a portion of the company. This means the founder will have to split profits upon the sale of the company with the investor and consult them when making important decisions for the company. The only way to regain ownership of the sold portion of the business is to buy the investors out, which will cost more than what was invested in the case that the startup succeeds (Banton).

Furthermore, equity financing comes in rounds, starting with the seed round, continuing on to raise Series A, B, C (and D+) funding rounds (Reiff). Founders should try to raise enough capital to grow the company to reach the next round of equity financing, which normally takes 12-18 months (Giglio).

Although there are no rules regarding how much a founder should sell, YCombinator suggests that founders should try to sell less than 30% of their company (Altman).

Further Understanding Equity

To grasp the full value of equity, this section will examine different stock types, dilution, and other implications regarding equity.

Preferred Stock vs Common Stock

Preferred stocks and common stocks are the two types of stocks, and the only difference is that preferred stock comes with rights that common stock does not have (Garcia). These rights are negotiated on a case-to-case basis between founders and investors (Ganti).

Preferred stocks’ rights are meant to provide investors with protection and help them secure a positive return on investment (ROI).

Although it is routine, it is not a rule that investors must receive preferred stock, and employees and founders receive common stock. All stock distribution is negotiated and may be different from a case-to-case basis (Garcia).

How Does Equity Get Diluted?

Equity dilution is another topic often misunderstood. Equity dilution at its core is not bad for founders, and it is unavoidable (Bloomfield). In an article published by Morgan Stanley, equity dilution is described as “the reduction of ownership as a result of new shareholders.”

When founders raise more equity financing rounds, (think series B, C and D+) they do not take away shares from previous investors. They also do not take shares away from themselves. Instead, they issue out new shares and because now there are more shares in the pool, everyone who owned shares before this new round takes place is getting their stake in the company diluted (Ralston).

More on equity dilution and preferred stock rights will be covered in chapter 8 of The Founder’s Guide to Fundraising.

Other Considerations

Finally, when raising equity it is important to realize the process is complicated, time-intensive, and expensive. The cost of raising capital through debt financing is cheaper than raising capital through equity financing. This is because, in the case of bankruptcy, debt holders are paid back before equity holders (Garcia), making equity a much riskier investment vehicle than debt. Investors who buy equity are therefore often compensated for this higher risk with higher returns, paid out by the company in one way or another (Majaski).

It is important that founders weigh the pros and cons of raising capital through both debt and equity financing.

Debt or Equity Financing

Equity remains a highly popular and contested form of financing in the modern startup industry, and for good reason. First off, equity has the potential to bring in far more cash than debt (Cremades). This is especially true for startups, as debt is a numbers-driven game (Garcia). For early startups, many do not have positive cash flow but still need financing.

Furthermore, equity financing does not add additional financial burden to the startup, which can be crucial in a startup's early phase (Majaski). Finally, investors who purchase equity are also incentivized to help the startup succeed as it maximizes their return on investment (ROI) (Cremades).

Pros and Cons of Equity Financing

Equity financing comes at a steep price. Giving up equity can result in losing control of a portion of the company. Profits must be split, and depending on what rights the issued stocks carry, investors may be entitled to the company’s earnings before the founder receives a single penny (Cremades).

Having partners also impacts the decision-making process within a company. If a founder does not retain enough board seats and voting power, they may find themselves being micromanaged at times and, on rare occasions, even replaced (Cremades).

Finally, raising capital through equity is a hassle logistically. Legal fees will cost thousands (Walker) and without the right connections, equity financing can become a huge time sink (Cremades).

Advantages of Equity Financing

The most obvious advantage of financing with debt is ownership being retained. This means the founder keeps all the profits and is in complete control of the company.

Furthermore, debt is a definitive liability. Loan repayments are predictable and completely quantifiable; once the debt has been paid off, the lender and the borrower’s relationship ends (Maverick). This does not, however, mean that all debt has fixed terms.

Founders should be careful when taking on debt, watching out for variable interest rates, maturing balloon debt, and revolving credit lines policies (Cremades).

Finally, taking on business debt can result in tax deductions, which can help companies maximize profit when positive cash flow is reached (Cremades).

Disadvantages of Equity Financing

The key downside of debt is that it must be paid back in both good times and in bad times. If debt is not paid back, the company may be looking at bankruptcy and/or have their assets repossessed (Chen).

When taking on debt, founders are essentially betting that they can repay the money in the future, regardless of how the economy is doing (Maverick). Because debt has predictable and quantifiable payments, it multiplies risk and reward, making the good times great, and the bad times awful. Taking on lots of debt means higher volatility for the company.

Finally, investors look favorably on companies with low debt-to-equity ratios when examining how a company finances itself (Maverick).

Convertible Notes

Throughout the years, convertible notes have become more and more popular due to their massive upsides (Raiten).

What is a Convertible Note?

A convertible note is debt that is later converted to equity. Through a convertible note, investors can loan a seed stage startup capital, but instead of receiving their money back with interest, they receive preferred stocks (Walker).

Because of the way the convertible note works, it allows investors and founders to deal with valuations later, normally when a series A is being raised. This is a big advantage as placing a value on seed companies where data is hard to conjure is difficult, leaving founders and investors often at odds (Walker). Moreover, convertible notes are faster than equity financing, and also have less legal fees.

Another upside for founders is that when issuing convertible notes, the investor rarely gets control rights (think board seats). This being said, convertible notes act like debt, and have interest rates, maturity dates, and events of default (DeGraw).

Finally, investors can negotiate for the note to carry various rights similar to a preferred stock, such as information rights, board observer rights, or investor specific requirements (DeGraw).

Converting Debt to Equity

How the debt is converted to equity depends on the conversion valuation cap or the discount term (DeGraw). These metrics are crucial to a convertible note, as without them investors and founders have misaligned incentives.

During a series A, founders are incentivized to maximize the company valuation, but without a cap or discount, the investors would be incentivized to minimize the valuation, as lower valuations would mean more equity and profit for the investor (Walker).

The conversion valuation cap and discount term play a part in determining how much equity the investor will receive as it defines a cap for how much the company can be valued when exchanging the debt into equity. For example, if the valuation cap was $5 million, but the valuation of the company was $10 million pre-money during the Series A, the debt would be able to convert for half the price the Series A investors were paying (Jepson).

Similarly, a discount example for a 20% discount would look like this: if other investors have to pay $1.00 for one share, the debt converts at a discount of 20%, so $0.80 would convert to one share (Jepson).

KISS and SAFE vs Convertible Notes

The SAFE and KISS are within the same family as the convertible note. Drafted and made open source by Ycombinator and 500 Startups respectively, these documents are popular alternatives to the convertible note (Ycombinator)(500 Startups).

The SAFE has many versions, allowing founders and investors to negotiate the valuation cap and discount. One version of the SAFE even has an MFN clause, but no discount and valuation cap (Ycombinator).

The MFN term provides investors with extra protection against events that may lead to their equity losing value (500 Startups)(Coltella). A popular example is a down round, which is when a company's valuation decreases in a subsequent round of financing.

Ycombinator also provides a pro-rata side letter which can be attached to any version of the SAFE. This pro-rata side letter allows the investor to purchase a proportionate amount of shares during the next round of financing, after the debt is converted to equity.

Meanwhile, the KISS only has two versions, the debt version and the equity version (500 Startups). The debt version has an interest rate and maturity date while the equity version does not.

Venture Capital (VC)

With hundreds of new funds being raised every year (Feng) and designated capital reaching unprecedented levels (Black), VC is undoubtedly an industry that is growing at an astonishing pace. Before exploring the opportunities presented by these firms a basic understanding of the business model of VC will prove useful.

VC firms are private and invest in early-stage companies for equity, hoping to make above-market returns.

However, firms do not invest their own money. The people who fund VC firms are called Limited Partners (LPs) and are normally high net-worth individuals, family offices, big corporations, or institutional funds (Takatkah).

With their newly acquired money, VC firms invest in early-stage companies, but because private equity is not liquid, VCs cannot pay back their investors on command. Instead, VC funds normally take 10+ years to pay back their investors (Dean).

Venture Capitalists will be explained more in-depth in further chapters of The Founder’s Guide to Fundraising.

How Do Venture Capital Firms Find Companies?

When picking early-stage companies to invest in, VC firms consider many criteria, but one hard requirement is the potential to explode. The reasoning behind this is deeply rooted in the VC business model. Given their 10+ years of lifetime, VC firms are expected to return at 3x (Dean). Due to the high risk associated with investing in startups, many are doomed to fail and therefore lose the VC's money.

The Pareto principle, stating that 80% of returns come from 20% of the investments, applies in the VC industry, so each investment a VC makes must have the potential to make up for the losses incurred from their other portfolio companies that fail (Dean).

Before attempting to obtain funding from VC firms, founders must make sure their startup satisfies this requirement.

How to Get Venture Capital Investment

To meet their ROI goals, VCs attempt to invest in “the next big thing,” and consider factors such as market, product, and management (McClure). Founders must be able to convince VC firms that their product has three key elements: the potential to change the world, a comparative advantage over any competitors, and a suitably large audience size.

Without an innovative product and large market size, generating high amounts of revenue and reaching the multi-billion dollar valuation that VC firms want will be challenging (McClure).

The most important factor VCs look at, however, is the management team. According to a study on VC firms conducted by Stanford’s business school, “the management team was mentioned most frequently both as an important factor (by 95% of VC firms) and as the most important factor (by 47% of VC firms)” (Stanford).

Founder’s Purpose and VC Incentives

Before engaging VCs it is important the founder remembers his or her purpose -- to secure enough funding for their startup until the next round of fundraising.

Sam Altman from Ycombinator warns founders that raising funds is not the same as being successful. He writes: “Raising huge amounts of money early on is very rarely how companies win (though it is sometimes how companies lose). Be one of those companies that does a lot with a little, instead of a little with a lot.” (Altman).

Another mindset founders should adopt before seeking venture capital is that the capital is meant to help companies “thrive”, not simply “survive” (Giglio).

Finally, founders should understand the incentives VC firms have before selling a portion of their company. The VC industry champions rapid growth, and not necessarily sustainability (Ward).

Although the VC industry is shifting to become more founder friendly (Blank), a VCs end goal is still to make profit and will want successful exits from their portfolio companies. This means two important things for the founder: 1) If you take VC money, you are accepting a liquidity event down the line (meaning IPO, acquisition, or merger) (Kanies), and 2) you may be removed from leadership positions in your own company. Indeed, a study conducted in 2003 found that only about one-third of VC-backed companies have a founder as the CEO at the time of IPO (Baker).

Of course, the industry has dramatically changed since 2003, and not all companies exit through an IPO. It is important to understand, however, that VCs are not actively looking to remove founders. Firing a CEO hurts the company’s image, in turn hurting the investment that the VC firm made (Jackson). It is important, however, that founders do not fear VCs, but understand their incentives and motives. In fact, VCs work hard to build and maintain positive founder investor relations (Jackson) and can provide powerful resources for founders.

Tips for VC fundraising

Fundraising from VCs can and should be difficult and stressful. A VC firm’s goal is to pick the cream of the crop. As such, saying “No'' to 99% of the offers is part of the job (Downey). These useful tips may help founders as they fundraise from VCs.

Be Aware of Investor Dynamics

The VC industry is an information game. The ties formed between people and the spread of knowledge is the water that makes the wheel turn.

When connecting with investors, founders should keep in mind the dynamics among the parties. If ‘xyz’ VC does not invest in a company, but offers to introduce the founder to ‘abc’ VC, the founder must realize that ‘abc’ VC may pick up on some signals. If ‘xyz’ VC did not invest in the company, this must mean that ‘xyz’ VC deemed the investment as not competitive, and ‘abc’ VC may use this piece of information when making decisions.

This case does not always apply though, for example, if ‘xyz’ VC focuses on series B & C investments, but ‘abc’ VC focus on seed or series A investments, this signal isn’t detrimental to the founder, and the warm introduction may even help the founder receive funding from ‘abc’ VC.

These signals are present everywhere, and although founders should not overthink them, it would do them well to understand the dynamics when building relationships (Suster).

Avoid Real Time Negotiation

VC managers negotiate as part of their job and will often be better at negotiating than founders.

Negotiating real time will pressure the founder and create a situation that favors the investor. Founders should not be afraid to ask for more time so they can carefully consider each set of terms. Also, founders should not be afraid of asking VC firms to clarify what certain terms mean or entail.

Don't Come Across as Desperate

Founders should create FOMO by stacking VC pitches together. When founders pack all their VC pitches together, it allows them to say phrases like “I’m talking to 10 firms this week, I don’t know when my round is going to close but I’m doing a lot of investment meetings.”

Also, founders can pitch to VC firms that they do not believe will invest in them to practice for the firms that they feel more positive about (Giglio).

Do Your Research

Finally, founders must do research on VC firms.

Sites like Crunchbase, AngelList, and CB insights provide information regarding VC firms. VC firms do not invest in competing portfolio companies, so founders should carefully study each VC firm's portfolio companies to avoid wasting time.

Venture Debt

Venture Debt is another source of capital available to startups and early stage companies.

What Is Venture Debt?

Similar to loans from banks, Venture Debt is a debt financing method that does not dilute the founders ownership (CFI). It's a great complementary financing method with Venture Capital, and gears towards serving early-stage companies that have not yet reached sufficient levels of cash flow to take loans from conventional banks (CFI).

Venture Debt can be extremely useful for founders to extend the time between equity funding rounds.

Unlike VC firms however, Venture Debt lenders are heavily focused on the numbers (Garcia). This implies that early stage companies applying for venture debt should have recurring revenue, and when asked about their decision making process, Venture Debt lenders identified the monthly recurring revenue (MRR) as the most important variable when determining the loan amount.

How Do Venture Debt Funds Work?

Venture debt funds commonly consist of loan amounts that fall between 2x to 12x the MRR of the early stage company (Chichi). Most early stage companies that receive Venture Debt loans have successfully raised Venture Capital rounds (Garcia), as this is an effective way Venture Debt lenders screen their applicants (Liu).

Other important materials a founder should be prepared to provide include the business articles of incorporation, financial statements, KPIs and metrics, along with the forecasted cash flow of the next 12 months (Garcia).

When forecasting cash flow, it is important to understand that Venture debt lenders are different from Venture Capital firms in that they want to see a founder’s confidence in paying back the loan, not necessarily a burning ambition to earn a massive amount of money (Garcia). Lenders may often demand covenants (Garcia) or warrants (CFI) as protection of compensation against the risks associated with lending to early-stage companies.

A covenant is a promise from the borrower to the lender that certain thresholds will be met (Hayes). A warrant grants the lender rights to purchase equity at a certain price before expiration (Chen).